In our most recent tea cupping, 9 cuppers evaluated 5 Japanese Sencha teas. The teas were sourced from multiple well-known vendors and varied in price from $0.08 to $0.36 per gram. This cupping was the fourth cupping by our expert Tasting Panel, with the goal of bringing us closer to validating and building consensus around ourTasting and Scoring Methodology.

If you’ve been following along, we have had 3 previous cupping events, the first covered 16 teas: 4 white, 4 green, 4 oolong, and 4 black, the second covered 6 black teas, the third cupping zoomed into the black tea category even further and covered 5 different Keemun Black Teas.

As our cupping activities are meant to get us closer to a consensus around our tasting and scoring methodology, we decided to zoom into the green tea category for this cupping and focus on a panel of 5 Japanese Senchas.

Sencha is arguably the most famous style of Japanese loose leaf green tea. It’s consumption is an everyday staple in Japan. In fact, Japan is well-known for the production of steamed green teas. Steaming the leaves during processing halts oxidation which results in dark green tea leaves packed with flavor. This differs when comparing processing methods to Chinese green teas which are primarily heated in a pan to arrest oxidation, resulting in a more nutty, subtle flavor. Sencha (煎茶), translates to steamed tea, and these teas pack an umami punch.

Variations in the steaming time are used to produce several variants of sencha. In order of length of steaming time, the variants are asamushi (light steam), chumushi (medium steam), futsumushi (normal steam) and fukamushi (deep steam). The steaming time often varies, so one tea maker’s fukamushi may resemble another’s chumushi. In general, the longer the steaming process, the less pristine the final leaves will be as the steaming process breaks down the leaf structure.

When choosing teas for this cupping, we did not take into account steam time, or harvest date. The teas were numbered 401-405 and sent to each person on the tasting panel to be tasted blind. Now let’s dive into the results and analysis:

- The average score for all samples by all cuppers was 83.5 points.

- The average high score by all cuppers for all tea samples was 90.2 points (i.e. “very good to outstanding,” according to our qualitative interpretations.

- The average low score by all cuppers for all samples was 76.8 points (i.e. “poor to fair” according to our qualitative interpretations.

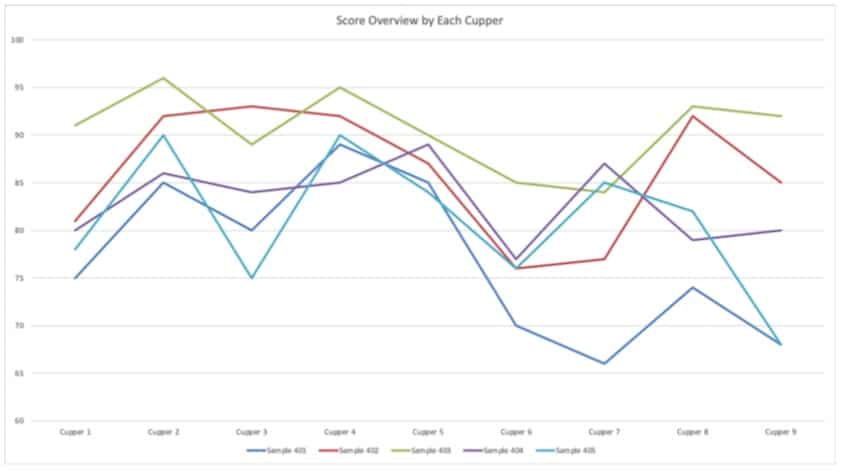

One of the ways we measure consensus is by looking at spread, which refers to the difference between the highest and lowest scores assigned to a tea sample by our cuppers. The average spread across all 5 teas was 17.2, roughly the same spread seen in our prior cupping. Spread ranged from a high of 23 (sample 401) points to a low of 12 (samples 403 and 404).

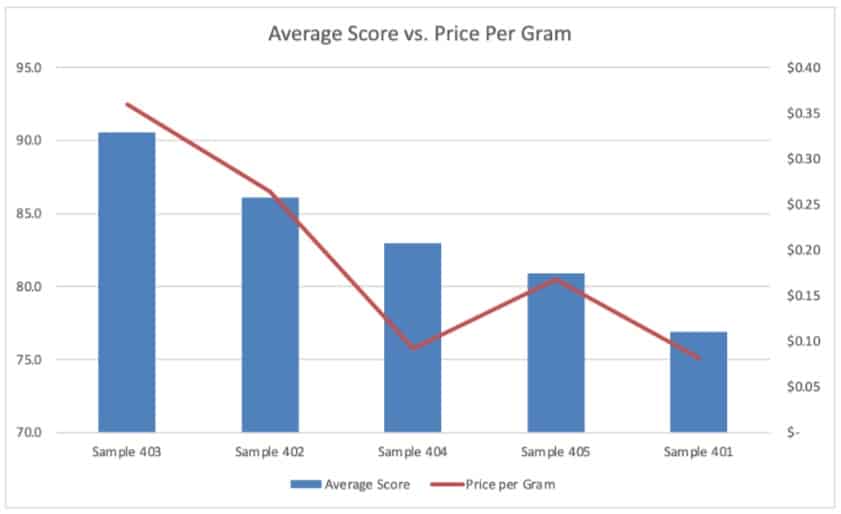

When looking at the average score for each tea sample, they placed in the following order:

- 403 with an average score of 90.6

- 402 with an average score of 86.1

- 405 with an average score of 83

- 404 with an average score of 80.9

- 401 with an average score of 76.9

As in the last cupping, there is largely consensus on the order of the teas from worst to best. This in itself fulfills the Tea Review Mission:

“Our mission is to help consumers identify and purchase superior quality teas, thereby increasing demand and prices, and ultimately rewarding farmers and tea companies that invest their time, passion, and capital in producing high quality teas.”

Given the spread of 5 teas, we know, as an average, which ones were superior. That said, there is still variance around what constitutes a particular number score. For example, given the maximum spread of 23 seen above with sample 401, one cupper’s 89 was another’s 66.

It’s interesting to note that also as in the last tasting, scores tracked pretty closely with retail price per gram overall.

Taking a deeper look into the scores by each cupper we see clearly the spread for each tea, and where the variance in sample 401 came to play.

If in future cupping activities, we seek to tighten the spread, we need to acknowledge that each cupper brings to the table his or her own experiences which they are judging against.

This can be clearly seen in the scores across multiple rounds of cupping, where some cuppers score lower on average and some cuppers score higher on average.

We can accept this, and see if the scores become more normalized over time as the panel experiences the same teas, or we can strive to discuss the intrinsic quality markers of each tea in hopes to find agreement on the component parts of a final score.